|

|

BY FEN MONTAIGNE

PHOTOGRAPHS BY GERD LUDWIG

From the outside the Institute of Mathematics in Akademgorodok looks much as it did in its Soviet heyday, a long, four-story, beige stone monolith that epitomized the intellectual might of the Communist regime. After the founding of Akademgorodok, or Academic City, in Siberia in 1958, this institute and several dozen others hummed with the research activity (hat undergirded the military-industrial complex and helped make the U.S.S.R. a superpower. In the 1990s, following the demise of the Soviet Union, the institute and Akademgorodok became symbols of a different kind—of the decay of Russian science and the decline of a great state. Government funding fell sharply, and impoverished researchers fled overseas or quit science in a massive brain drain.

But walk into the Institute of Mathematics today, ten years after the collapse of the U.S.S.R., and something intriguing is taking place. I strode down a long, dark corridor that, with its mustard-colored walls and peeling brown linoleum floor, exuded a Soviet shabbiness I had come to know as a Moscow correspondent in the era of Mikhail Gorbachev. Soon, however, I entered another wing of the institute and plunged into a different world. Young workers, most of them under 30, sat behind computers in offices newly renovated with white tile floors and pale wooden desks. A handful of people relaxed in a room with plants and a small waterfall. Across the hall, in a modest office, the 29-year-old CEO of this enterprise—a 500-person computer software company called Novosoft—was furiously tapping out e-mails as his eyes darted between the computer screen and several visitors.

Founded in 1992, Novosoft—which does computer programming for foreign firms such as IBM and creates new software applications for mobile phones, websites, and other technologies—has enjoyed explosive growth since 1998. It is one of many new high-tech companies that have sprung up in Akademgorodok's research institutes, where fledgling enterprises can draw on a large pool of talented physicists, mathematicians, and computer scientists and offer their services, relatively cheaply, to the West and Japan. In this city of 130,000, dubbed "Silicon Taiga," young workers can earn as much as a thousand dollars a month—many times what their parents usually make and enough to keep most techies from emigrating.

I asked the CEO, Serge Kovalyov, a restless, dark-haired man with an excellent command of English, if he had ever considered leaving Russia. Letting out an explosive laugh, he replied, "Me! Is there anything better that can be offered me than creating the new Russian economy?"

Down the hall one of the founders of Novosoft, Vladimir Vaschenko, said he and Kovalyov were building more than a company. They were helping create a new Russian society.

"What we are doing in our company is growing a middle class," said Vaschenko, 36. "Everyone in our company is middle class -they have enough money to enjoy a good meal, they have a nice place to live, and they have a car. They feel life is stable, and they feel they have room to grow in the future."

Vaschenko acknowledged that even in Akademgorodok, with its highly educated workforce, the emerging middle class makes up less than 10 percent of the population. And while he thinks the middle class will continue to expand, he is mindful that, given Russia's history, much could still undermine the country's excruciatingly slow climb out of the post-communist economic morass.

"If 15 years from now Russia is in the same state as today, I may feel there is no hope for the future of the country," he said.

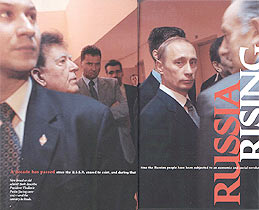

A decade has passed since the U.S.S.R. ceased to exist, and during that time the Russian people have been subjected to nothing less than an economic and social revolution. Three-quarters of state enterprises have been fully or partly transferred to individual owners in a corrupt privatization drive. The Soviet social safety net has been shredded, and articles about the woes and impoverishment of the Russian people could fill volumes. But as a seven-week trip around Russia earlier this year showed, shoots of new life are springing up throughout the country.

Most of Russia's economic activity is centered in Moscow, where a sizable middle class has emerged. Yet vibrant businesses also have taken root in many other cities, including Novosibirsk, Nizhniy Novgorod, St. Petersburg, Samara, and Yekaterinburg. Often the most successful enterprises are in spheres of activity that scarcely existed in the Soviet Union, such as computer software, sophisticated food processing and packaging, restaurants, and advertising. Ironically, the collapse of the ruble in 1998—which made imports prohibitively expensive—boosted domestic production. That increase, coupled with higher prices for Russian oil and gas, has at last halted the country's economic slide; the economy grew by 5 percent in 1999 and by 8 percent in 2000.

That said, the financial success stories—and the middle-class workers affiliated with them —are still islands in a sea of stagnation. The official salaries of most Russian workers hover around a hundred dollars a month, although many earn some undeclared income on the side. An estimated 20 million of Russia's 145 million people live below the official poverty line of $31 a person a month. Tax evasion is epidemic, and an estimated 25 to 40 percent of the economy is conducted underground. And every year a tiny layer of super-rich Russians— fearful of general instability and a shaky banking system—ships an estimated 20 to 25 billion dollars out of the country to foreign banks, much of it from the sale of Russia's abundant natural resources.

RUSSIA TODAY Most of the population of the planet's largest country is packed into its west and along the Trans-Siberian Railroad. The government divides the country into seven districts (below). Many of Russia's valuable natural resources are in the remote north, creating rare islands of relative prosperity such as Yamal-Nenets, rich in oil and gas, and Sakha, source of 98 percent of Russia's diamonds. |

Still, to focus solely on the myriad problems is to ignore what has been accomplished in a mere decade. And, as I have discovered after a dozen years of writing about the former U.S.S.R. and being whipsawed by bouts of optimism and pessimism, you must be able to hold in your mind the dichotomy of the two Russias. One is a place of well-educated, hardworking people slowly building a humane society and the other a land where a worn-out populace endures corruption and a lack of decent civil institutions. The question is, will the second Russia overwhelm the first, or will the new Russia ultimately prevail?

One thing is certain: What is happening from the bottom up in Russia is far more encouraging than what is happening from the top down. At the top the crony capitalism that enabled a small number of oligarchs to become fabulously wealthy during privatization in the mid-1990s still continues under President Vladimir Putin, only with a somewhat different cast of characters. Putin is extremely popular with most Russians, enjoying a 70 percent approval rating. But many reformers view the president—a former KGB colonel—as a cautious man with little commitment to democracy or a free press and little stomach for tackling critical problems like endemic corruption and the creation of a viable legal system. He also continues a war in Chechnya that is draining the country's treasury and spilling the blood of its citizens.

"Russia's like a rusty ship," said Boris Nemtsov, leader of a liberal party in the Duma, or lower house of parliament. "It's barely floating, and instead of trying to repair the ship, Putin just grabs a bucket of paint and starts painting it in patriotic colors. That's the essence of Putin—he won't do anything fundamental. The security services, the police, the prosecutors—he won't touch these elements of the Soviet system."

Despite the lack of reform in Russia's woeful institutions, such as the courts, many individuals are engaged in building a more stable society. Small businesses are slowly increasing, larger businesses are becoming more efficient, and students are pouring into colleges and universities. And these days in Russia youth is everything. In few countries is the generation gap as wide or are people under 35 playing such an important role in transforming society. Unencumbered by communist thinking and work habits, unaccustomed to the Soviet Union's cradle-to-grave security, young Russians more readily accept the challenges and uncertainty of a market economy.

"Your prediction for the future mostly depends on your age," said Novosoft's Vaschenko. "People our age have more hope. Most people still managing the institutes in Akademgorodok are older than 50, and they still rely on the government to help them. We rely on ourselves. We know how to earn money, and what I'm waiting for is the time when these old people will be replaced by us. When we do that, I think Russia will be a better place."

Vaschenko is right to think in terms of generations, for the transformation of Russia will take far longer than most people imagined. The euphoria of a decade ago has been replaced with a cold-eyed realism and an understanding that turning Russia into a civil society, with an effective market economy, is a herculean task—and not just a matter of grafting Western models on this unruly land.

"All this will take a long time, at least three generations," said Dmitri Trenin, deputy director of the Carnegie Moscow Center, a think tank. "Well, we're halfway through the first one. Just two-and-a-half more generations to go."

Kirill Dmitriev and Peter Panov don't have that kind of patience. Born and raised in Ukraine and Moscow, respectively, they graduated from top American universities and worked in some of the United States' most prestigious companies—such as Goldman Sachs and Qualcomm—before deciding to return home and cast their lot with a reborn Russia. Dmitriev, 26, graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Stanford University and Harvard Business School. Panov, 31, attended the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School on full scholarship, receiving his M.B.A. in 1996. Though these two men could have stayed in the U.S. and earned loads of money, they returned to Russia in 2000 for two reasons. The first was the sense that they had an important role to play in shaping Russia's new economy. The second was Anatoly Karachinsky.

A low-key, bearded, 41-year-old partial to wearing khakis and cowboy boots, Karachinsky is the president and CEO of Information Business Systems (IBS) Group, one of the country's most successful information technology companies. A computer whiz during the waning days of the Soviet Union, Karachinsky founded his own firm in 1992 and quickly became a master at designing and selling the sophisticated computer systems that integrate the operations of large businesses, such as Sberbank, the state savings bank. Karachinsky's IBS Group now employs close to 2,000 people and adds another few hundred every year. Its revenues increased by 50 percent in 1997 and in 1999.

Brainpower: Physics gather for a daily roundtable meeting in Akademgorodok, or Academic City, a utopian Sovie-era community in Siberia built to gather the nation's top scientists. Now that state support for research is drying up, their ideas help run their own fleet of business enterprises. |

Seeking good managers, Karachinsky made Dmitriev and Panov an alluring offer that included the opportunity to link some of Russia's industrial giants through an Internet supply-and-sales network.

"Peter and I had tremendous possibilities in the U.S.," said Dmitriev, a tall, exuberant man with light brown hair. "But we came back because we feel it's our home, and there's a certain responsibility that goes with it. We're playing a real role in this country as it grows. The level of influence we have is so much greater than we'd have in the U.S."

I met the pair in IBS's Moscow headquarters, a modern, glass-and-concrete building set back from the capital's grimy Dmitrovskoye Highway. Like some other young Russian business people, Panov and Dmitriev believe that the robber baron phase of Russian capitalism is gradually fading as oligarchs seek legitimacy.

"Up to now, money has been made by people dividing up different pieces of the old state pie," said Dmitriev. "The oligarchs were thinking, 'How can I take away this guy's piece of the pie?' Now the pie has been more or less divided up, and the oligarchs are thinking, 'I can't take this guy's pie because he's too powerful.' So they want to grow their piece of the pie, they want good managers running their businesses, and they want respect, because in Russia it's all about respect."

Panov interjected, "Their horizon used to be really short. During privatization they wanted to take what they could and get out. Now their horizon is way, way longer."

And that, Dmitriev and Panov say, is where they and IBS come in. Karachinsky is banking on it, and one afternoon as I talked with him in his office, he served up the most cogent analysis I'd heard of the Russian economy: "There is the old economy of the U.S.S.R., and it has a much tougher road. Many enterprises will first have to die to be reborn. Then there's the resource economy—oil, gas, aluminum—a large part of the gross domestic product. It's making a good profit and moving ahead. Then there's the new economy, the economy that didn't exist ten years ago, and we're part of that.

"If you just focus on the old economy, the country looks in terrible shape," said Karachinsky. "But something entirely new is being born here. Russia is just at the beginning of an economic climb. Overall, I'm pretty optimistic."

[...]

RUSSIA

RISING

RUSSIA

RISING